“The potential changes to particular provisions of the current PSM standard that OSHA is considering include: 8. Clarifying paragraph (e) to require consideration of natural disasters and extreme temperatures in their PSM programs, in Response to E.O. 13990.” — OSHA, 20-Sep-2022 call for Stakeholder comments

I grew up in the Midwest. I’ve lived in Joplin, Kansas City, Tulsa, Wichita, and now in St. Louis. Tornadoes have been part of my life since early childhood. I remember as a little boy sheltering with my family one afternoon and seeing a tornado on the distant horizon through one of the basement windows. We all knew what to do in a tornado emergency: Stop what you’re doing. Open the windows so the house is less likely to get blown out. Go to the basement. Shelter under the stairs, next to the concrete foundation. Stay away from windows. Pray that the tornado misses you anyway.

We always understood that tornado season was April through June, so the tornado drills at school were in February or March. For a kid, tornado drills were a welcome break from classes.

I miss tornado drills. When they think about it, most adults do. Not for nostalgia, but for the safer workplace they create.

The Supercells of December 10 and 11, 2021

On December 10, 2021, supercells spawned a total of 71 separate tornadoes, tracking from Missouri into Illinois, and from Arkansas into Tennessee and Kentucky. They included two EF4 tornadoes and six EF3 tornadoes, which together killed 89 people directly. Alabama, Indiana, Georgia, Mississippi, and Ohio were also in the paths of some of these tornadoes, although the tornadoes in these states were mild (EF0 or EF1), if any tornado can be considered mild.

Three industrial workplaces were hit by these tornadoes. In Bowling Green, Kentucky, shortly after 1 am on December 11, GM’s Corvette Assembly Plant suffered significant physical damage—extensive roof damage, including to roof-top HVAC units, and a guard shack that was obliterated when it was struck by an EF3 tornado. No deaths or injuries were reported at the plant, but elsewhere the tornado killed 16 people directly and one person indirectly.

Earlier that evening an EF4 tornado travelled over 165 miles long and killed 57 people along the way. On its 3-hour path of destruction, at around 9:30 pm, the tornado struck Mayfield, Kentucky, home of Mayfield Consumer Products, a candle factory. Eight employees of MCP were killed at work in the tornado.

Still earlier that evening, at around 8:30 pm, an EF3 tornado hit the Amazon warehouse in Edwardsville, Illinois. It flattened the tilt-up concrete building, which fell inward, killing six of the seven workers sheltering in the bathroom at the south end of the building.

Public Outrage

Altogether, 89 people died during this tornado outbreak. The outrage, however, centered on the workplace deaths at the Amazon warehouse and the Mayfield Consumer Products candle factory. December 2022 was marked with many remembrances and calls for change.

The two incidents have much in common. Neither facility had designated storm shelters. Instead, workers, when they were finally released from their tasks to find shelter, were directed to restrooms or hallways. Workers at both facilities reported that the evening supervisors told them after tornado warnings were issued that workers who left to find adequate shelter would lose their jobs. And both facilities were found to have inadequate or barely adequate emergency response procedures and training in place.

The landlord for the Amazon warehouse in Edwardsville is rebuilding to “pre-loss conditions”, meaning that there is no change to the structural design. It was originally built to current code, so there will still not be a tornado shelter. After completion, facility restrooms will still serve as “sheltering areas”.

OSHA investigated the Edwardsville incident and recommended that Amazon review its policies and procedures for severe weather but issued no citations or fines. Kentucky OSHA investigated the Mayfield incident and issued several citations and violations. Mayfield Consumer Products is now being investigated again for retaliating against employees who cooperated in the original investigation.

For many, then, there is ample reason for outrage. But outrage is not risk.

How Much Risk Does a Tornado Pose to a Facility?

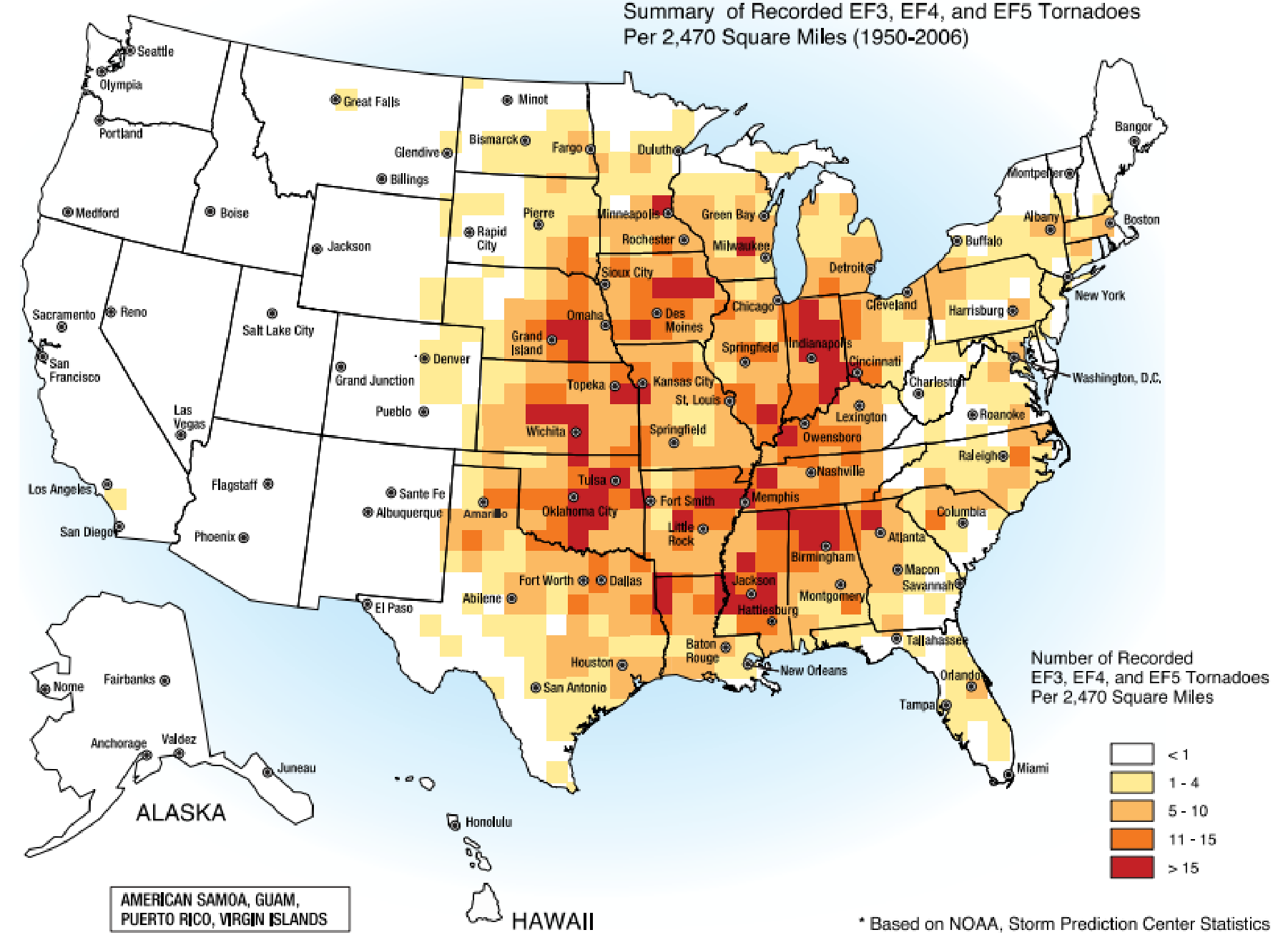

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration tracks all kinds of weather events, including tornados. Figure 1 shows a map with the number of killer tornados—EF3, EF4, and EF5—per 2,470 square miles over the course of 57 years.

Figure 1.Total Tornado Activity in the United States – 1950 to 2006 (source: NOAA).

The most extreme zones on the map are those with more than 15 killer tornados during the 57-year period. Using a conservative methodology from Process Safety Progress, we can see that the mean time between killer tornado strikes on any particular facility in those zones is more often than once every 2,000 years. If such a strike results in 5 fatalities per incident in the absence of adequate storm shelters, the risk of tornado fatalities is greater than 0.0025 fatalities per year. The most tolerant risk criteria we have ever seen is 0.01 fatalities per year. More commonly, however, risk tolerance criteria are anchored to 0.001 fatalities per year. Or less.

What does that mean? Depending on what its risk tolerance criteria are, a plant in the most extreme zones on the map will probably have to conclude that a tornado shelter is required to reduce risk to a tolerable level.

As for the Amazon warehouse, Edwardsville is in the second most extreme zone (“11 – 15 tornadoes”), with a mean time between killer tornado strikes on a specific location between once every 2,000 years and once every 2,500 years. Using the same criteria, that equals a risk of between 0.0020 and 0.0025 fatalities per year. By the same logic, it appears that most workplaces in that zone—not just the Amazon warehouse in Edwardsville—can only achieve a tolerable risk by providing a tornado shelter, unless they are unusually tolerant of risk.

Mayfield, just south of Paducah in the far western tip of Kentucky, is in the third zone (“5 – 10 tornadoes”), with a mean time between killer tornado strikes on a specific location between once every 2,800 years and once every 5,600 years. This means a risk of between 0.0009 and 0.0018 fatalities per year. It is only in this zone that a reasonable argument can begin to be made that the risk is low enough to justify not building a tornado shelter.

Response to Disasters

While the incidents at the Amazon warehouse and at the Mayfield Consumer Products candle factory were similar, the responses afterwards were very different. Mayfield allegedly obstructed the investigation and allegedly retaliated against their employees that cooperated with it.

Amazon, while not insisting to their landlord that a tornado shelter be included in the reconstructed facility, has committed to emergency drills and manager training, according to local reporting. “They have increased manager training, required two drills every quarter and issued cards to every employee on how to stay safe in severe weather.”

It tends to take a catastrophe to prompt change. If the risk is too high now, it was too high before the tornadoes of last December. Not just for the facilities that had the bad luck of being hit, but for every facility in their region. In hindsight, pundits and the popular media are quick to say, “they should have known.” Right. We’ve known for decades that killer tornadoes can strike just about anywhere in the United States east of the Rockies. Last December’s outbreak of tornadoes was not news; it was just a reminder.

OSHA’s Response

OSHA did not cite Amazon because OSHA does not have a standard requiring severe weather emergency plans. It does have 1910.38 – Emergency action plans, which requires every employer to prepare an emergency action plan. Except for fire, however, it doesn’t stipulate what kind of emergencies to plan for.

In a letter of interpretation about the HazWOpER standard, however, OSHA does state that workplaces “located in areas prone to natural phenomena, such as earthquakes, tornadoes, and hurricanes, and subject to a ‘substantial threat of release of hazardous substances’ are covered by 1910.120… and if so incorporate emergency response procedures to such natural phenomenon in their emergency response plan.”

So, while OSHA may have felt that it had no basis for citing Amazon, they would have no hesitation to cite and fine facilities using and storing hazardous substances. The rulemaking that OSHA is currently engaged in to update the PSM standard will make it explicit for the process industries.

Plan and Prepare

As you have considered the safety of your plant, have you taken tornadoes into account? It’s not too soon; last December’s deadly outbreak of tornadoes should serve as a warning. But warnings only do any good when heeded.

So, if you don’t have adequate tornado shelters at your facility, it’s probably time to start including them in your capital budgets.

At the very least, though, do what Amazon is now doing. Make sure that your policies and procedures are real and up to date. Make sure your managers and supervisors, especially those leading your facility during the off shifts, know exactly what to do during a tornado watch and during a tornado warning. Don’t make them dependent on calling the plant manager or corporate. Train your employees, so they know exactly what to do during a tornado watch or warning, in case the chaos of the moment disables lines of communication.

And drill. Amazon claims they are going to drill twice a quarter. It’ll be interesting to see if they keep that up after the heat of the moment passes but drilling at some frequency is essential to keeping everyone alert and prepared. It might not be quite as fun as it was when you were in elementary school, but it is just as important.