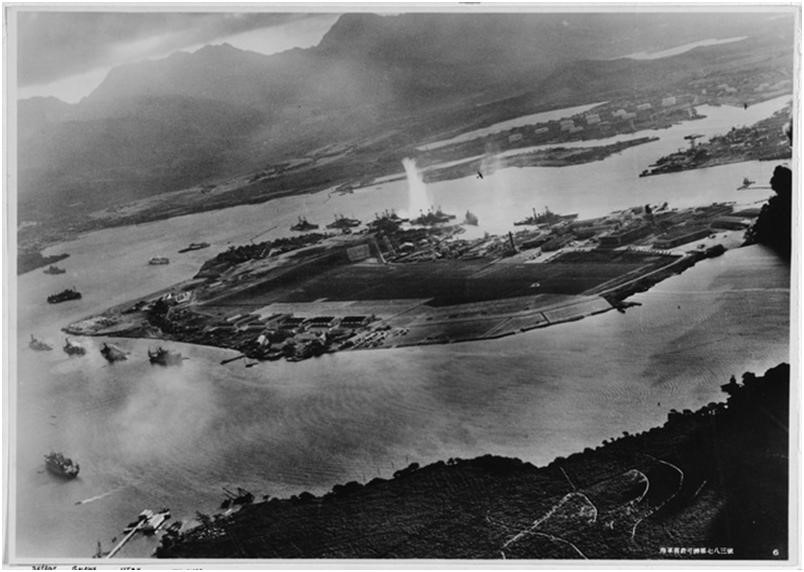

“Air raid, Pearl Harbor. This is not a drill.” —Lt. Cmdr. Logan Ramsey, 7-Dec-1941

‘Beauty’ Ramsey sent one of the most famous telegrams of history after watching a Japanese dive bomber’s payload detonate in Pearl Harbor. Other telegrams went out that morning, from the Navy Yard and Kaneohe, but they were largely ignored until smoke from burning ships was visible for miles.

Why Isn’t An Alarm Enough?

Why did Ramsey believe it necessary to explicitly state that “This is not a drill” in order to get personnel to take it seriously? Shouldn’t the response have been the same whether it was a drill or not? Given the lack of response to other warnings, Ramsey’s belief was spot-on. But why?

Aside from alarm flooding, when there are more alarms coming in than a person can hope to manage, there are typically three reasons that personnel do not respond to alarms with urgency:

- Belief that it is a false alarm

- Belief that it is a drill

- Belief that they have time to finish what they are doing first

False Alarms

A few years ago, I was at a conference. A safety conference. Each day had an opening plenary session in a huge ballroom. On the second day, about 15 minutes into the plenary speaker’s presentation, an alarm went off. No flashing lights, just an insistent audible alarm. The speaker ignored it and continued to deliver his prepared remarks. Some people began to look around nervously, but neither the speaker nor the session chair said anything.

After a moment, I realized how embarrassed I would be as a safety professional to die in a hotel fire because I ignored a fire alarm. So I got up, pardon me’d my way down the row where I was sitting, and exited down the center aisle to the doors at the back of the room. On my way out of the room, I said “You guys are probably right. It’s probably a false alarm, but I don’t know that.” My voice was so low, though, that I’m not sure that more than a half dozen people even heard me.

Out in the corridors, the alarm was still sounding, but there was no evacuation going on. People were not streaming from the other ballrooms or meeting rooms. Down the main stair case and out the doors to the sidewalk outside the hotel, there was the alarm, but no flurry of activity. I stood outside the hotel for a full minute before anyone else exited. After a while, all the conference attendees—about a thousand safety professionals—were standing out there with me. A few minutes later, the alarm quieted.

About 10 minutes total passed from when the alarm first sounded before someone from the conference center came out and announced the “all clear”. It had been a false alarm. A contractor had bumped something.

On the way back in, I asked another attendee what had prompted everyone else to leave. He said, “The session chair stopped the speaker, promising him that we would resume where he had left off, and then told everyone that they should probably exit the building until the hotel management explained what was going on.”

Drills

For many, the last time they participated in a drill was during a school fire drill. The NFPA recommends a school fire drill at least once per month that school is in session. OSHA requires that every employer have emergency action plans, but does not require that there be drills. Some organizations do have drills, though, especially those in high hazard enterprises. A school fire drill was a lark, a welcome interruption to the day. For most, a workplace drill is an unwelcome interruption to the day.

Drills are not the same as false alarms. One of the purposes of drills is to assure that personnel are practiced at responding to alarms, which false alarms also achieve. Another purpose of drills, however, is to evaluate the effectiveness of emergency response procedures. Evaluation requires planning, and a false alarm does not provide the opportunity to plan. Any evaluation following a false alarm can be no more than a partial evaluation.

Drills are evaluated, however, or at least they should be. Most personnel are clever enough to discern what is being evaluated, at least as far as their own conduct is concerned. They will make a half-hearted effort to comply with the requirements of the drill, but focus primarily on the aspects of their own performance being evaluated. For many, this typically consists of no more than assembling at the designated muster point and not being the last person there. They don’t become fully engaged because they don’t want to complicate their return to work when the drill is over. Some will not participate at all, deciding that what they are working on “is more important than any damn drill.” Worse, those evaluating the drill will sometimes excuse non-participants because they agree with their priorities.

Plenty of Time

In its website, Fireco quotes evacuation expert Ed Galea describing a 1979 fire at the Woolworths in Manchester, UK: “People who had purchased and paid for their meal… Even though they could see the smoke, they could smell the smoke, they could hear the alarms going off, they felt they had sufficient time to complete their meals before evacuating.” The account goes on to report that 10 people died in that fire.

They didn’t feel a sense of urgency. Urgency is not panic, which is borne of fear. Calm is the antonym of panic. We want people to be calm during an emergency. We also want them to be urgent, because the antonym of urgency is complacency.

Bellwethers

When an alarm sounds, people look around to see what other people are doing. No one wants to appear foolish, and responding to an alarm when others are not seems foolish. If you have ever been staying in a hotel when the fire alarm went off, you probably noticed that guests were slow to open their door. Then, instead of evacuating, they were out there to check out what was going on. After checking with the others milling about in the corridor, they either returned to their room or reluctantly followed someone to an exit—but only if there was someone else already exiting.

A bellwether is a sheep, usually with a bell on its neck, that leads the flock. It is not so much a trendsetter or harbinger, manager or director, as it is a leader by example. People, like flocks of sheep, need bellwethers to encourage them to do what should be done. This requires that bellwethers know what should be done and be committed to doing it themselves, because bellwethers lead by example.

When the Alarm Sounds

Those of us with responsibilities for the safety of others have a special obligation to be bellwethers, to lead by example. When an alarm sounds, most people will not respond as they should unless they get confirmation. Even additional proof that the alarm is real may not be enough—people need leaders. Be prepared to lead, and don’t wait for someone to tell you, “This is not a drill.”